By Dr. Jeffrey Keimer

The following post contains affiliate links through with YFP or its team members may receive compensation.

This is a guest post from Dr. Jeffrey Keimer. Dr. Keimer is a 2011 graduate of Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences and pharmacy manager for a regional drugstore chain in Vermont. He and his wife Alex have been pursuing financial independence since 2016. Check out Jeff’s book, FIRE Rx: The Pharmacist’s Guide to Financial Independence to learn how to create an actionable plan to reach financial independence.

When you buy something, would you rather pay full price or get it at a discount?

Well, unless you wear paying full retail as some sort of weird badge of honor, I’m willing to bet you’d rather go with the latter; and to be sure, there are many ways to get stuff for less. You could shop the clearance rack, buy in bulk, and maybe even haggle.

But what if, after you’ve tried all those things, you’d still like to pay less? Enter the credit card reward point. Ever since the concept was introduced back in the mid 1980s, consumers have been able to get reimbursed for bits of their purchases and do just that, get what’s effectively an additional discount. And, if you play your cards right (pun fully intended), that discount can be incredible.

In this post, I’ll teach you how to play the credit card rewards game, and make no mistake, it is a game and the prizes get better as you get more advanced. At its basic level, credit card rewards can help you pay a bit less overall for the things you buy on a daily basis. But at the game’s highest level of play, so-called travel hacking, you can exploit these programs to travel the world in luxury for free.

Interested?

Cool.

In a nutshell, the rewards game comes down to two things: earning and redeeming. For each, I’ll cover some of the common strategies, broken down by difficulty, that you can use to maximize rewards in a way that works for you. Don’t want to go down the full travel hacking rabbit hole and start a Tik Tok about free first-class travel? Then don’t. The rewards game can be lucrative even at the beginner level with minimal effort.

Before we get into all that though, we need to talk about the ways you can lose the game.

Ways to Lose

First and foremost, when dealing with credit cards and the reward programs surrounding them, don’t think for a second that the companies offering these benefits are losing money with them. Just the opposite. Credit cards represent one of, if not the, most profitable parts of the banking industry and rewards cards are no exception. And while rewards give us the opportunity to take back some of those profits for ourselves, the way you lose here is the same way everybody else loses.

How?

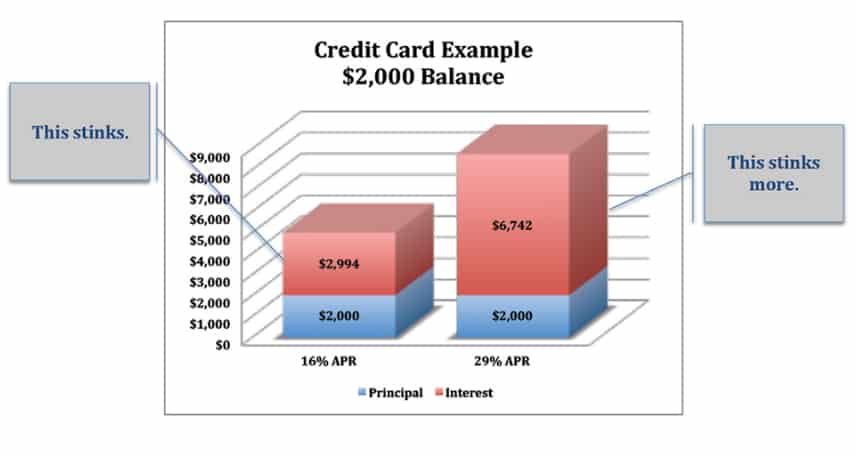

First and foremost, credit cards charge people exorbitant interest when they carry a balance. This is even more so with rewards cards since they generally charge higher APR’s and fees than non-rewards cards. Because of that, it is extremely important that if you plan on playing the rewards game you’re in a position to pay your balance off in full each and every month.

Have trouble with that or are you currently in credit card debt? DO NOT PLAY THIS GAME!

Second, people tend to spend more when using credit cards than they do when using cash alone. Why? While the jury is still out on the exact cause, recent research suggests that the dopaminergic reward pathways in the brain are involved. Yeah, those pathways! Turns out the old phrase “shopaholic” might be pretty spot on.

Once you add in the prospect of other rewards to your shopping, it’s not hard to see why banks push rewards cards. Rewards cards generally charge merchants a higher fee when you use them and finding ways to get you to spend more is insanely profitable. Your job, if you decide to play the rewards game, is to resist. Remember, the point here is to get a discount on your normal spending so you can free up money for other goals, not inflate your lifestyle. Rewards can be great, but not if they come at the expense of blowing up your budget.

Finally, I wouldn’t recommend playing (at least not aggressively) if you plan on getting a serious loan, like a mortgage in the near future. Opening up a number of credit cards in a short period of time, as many travel hackers do, might spook a loan officer resulting in a denial of your loan application.

Earning Rewards

As I said before, the game involves two parts: earning and redeeming. In this section, I’m going to talk about some of the most common ways people earn points, miles, cash back, even crypto (all of which I’ll refer to as “points” for simplicity’s sake for the rest of the article) and break down each strategy by its relative difficulty in practice. What follows is by no means an exhaustive list, but should help you get started and decide how deep down the rabbit hole you want to go.

Beginner

Points/Cash Back on Purchases (One Card)

This is probably what most people who dip their toes into the realm of credit card rewards do. You open a card that earns points on every purchase and put pretty much all your spending on that card.

Simple, right?

It is. The only complexity here comes down to what card you choose to use. First, you need to decide if you want your points to pay for travel or act as cash back (typically in the form of a statement credit). In terms of overall redemption value, travel tends to come out on top here, but like anything, there can be nuance. Sometimes going for the cash-back card can make more sense depending on your lifestyle.

Second, you need to decide whether or not you’re open to a card with an annual fee. If your plan is to use the points for travel redemptions, it’s almost certain that you’re going to need one with an annual fee since many of the most lucrative redemption options will be closed off to you in the no-fee tier of cards. If, on the other hand, you’re going to redeem your points for cash back then a no-fee card can work just fine.

Third, you need to decide what kind of points you’re looking for. That’s going to depend on how you see yourself redeeming them. Many points limit what you can do, only letting you use them for cash back or with a particular business. On the other hand, some points, such as those issued by the various card issuers themselves, can offer a wider range of flexibility. That flexibility often comes at the cost of an annual fee though, so bear that in mind.

Finally, you need to pick an individual card. The choice here simply needs to line up the points you want and their earning rates with what you actually spend money on in your budget. Like to eat out and order food? Make sure to look for a high earning rate on dining expenses. Fly a lot? Find a card that offers a high rate on travel or consider a card with your favorite airline. It’s not rocket science. And if nothing in your budget really sticks out as a “bonus category” for you, then look for a card with a high base earnings rate. These days, there are a number of cards that offer 1.5-2% back on all purchases, usually without an annual fee.

Once you’ve done all this and picked a card, you’re good to go. You won’t be writing a travel hacking blog, but you’ve gone from zero to something in the rewards game. And while you may decide to go no further (nothing wrong with that), following these steps to evaluate new cards is fundamental to the higher levels of play.

Sign-Up Bonus (SUB) Targeting

Out of all the point-earning opportunities, the most lucrative BY FAR is the SUB.

And just how lucrative can a SUB be?

Well, as I’m writing this, I’m finishing up one that offers 80,000 points on $4,000 worth of spending in the first 3 months. Given my history with these points, I generally get around 2.5 cents worth of value from each of them bringing the total value of the SUB to $2,000. That’s a 50% return on that spending!

When it comes to the rewards game, SUBs offer the greatest chance to generate value. Therefore, any strategy approaching the rewards game should take them into account; even if you only plan on opening a single card.

At the beginner level, interacting with SUBs is a little different than the more advanced levels and, paradoxically, requires a lot more thought up front. This is because you’ll be targeting a SUB on a card you plan to keep versus one you’ll likely close. As such, when thinking about SUBs at this level, you want to target a specific type of card first, then target the best SUB within the list of cards meeting your criteria.

The benefit to approaching SUBs this way is that you don’t really have to worry about all the other little (and often unsaid) rules that come along with SUBs. Just open the card you want, meet the SUB criteria (if there are any), then enjoy keeping and using the card. That’s it.

Intermediate

Got your feet wet with a new card and want more? Cool. Personally, this is the level where I operate for the most part. If you like to travel, success at this level can help cover a significant portion of that part of your budget.

Before getting into that, a disclaimer. At the intermediate level, we’re going to start getting into the weeds regarding some of the “rules” surrounding credit card openings. I’m going to be a little vague here, and that’s intentional. Many of these so-called rules are based on guidelines used by credit card companies (often not published publicly) to determine whether or not you’ve run afoul of their terms of service; prompting them to take away all your points and cease doing business with you. Those terms of service (particularly in areas such as program misuse) tend to be intentionally vague themselves, so I’m going to follow suit here.

Multi-Card Optimization

Let’s say you started off your rewards journey with a single card. Maybe that first card gave you a dope 6% back on groceries. Sweet! But when it comes to dining out, you get a measly 1% back. Meanwhile, there are cards out there offering at least triple that in the category with no annual fee! Using one card for all your spending certainly has the perk of simplicity, but I can guarantee you that you won’t be able to maximize your point earnings with just one card.

Cards are typically good for covering one or two spending categories, but not much more than that. This is where a strategy of using multiple cards to cover the gaps can come into play, especially if those additional cards don’t carry an annual fee.

In practice, this might mean you have four or so cards, each with a different role to play. Going out to eat? Use the card that gets triple points on dining. Filling up the car? Pull out the one that gets 5% back at the pump. You get the picture.

Depending on what cards you use, there can also be some additional synergies here too. For example, Chase Bank’s in-house reward point, the Ultimate Reward (UR) point, can be earned on a number of their no-fee Freedom cash back cards. However, the UR point you’d earn with those is the same UR point you’d earn with their premium tier Sapphire cards. When paired with one of the Sapphire cards, the value of those points can go up significantly. Given the fact that those no-fee cards can earn significantly higher rates than the Sapphire card in certain places, the multi-card strategy can really bump up your earning potential.

The only real difficulty with a multi-card strategy (and my wife likes to remind me of this) is that it can be tough to juggle multiple cards and remember what to do with all of them at any given time. This is especially true if you (like me) incorporate one of those cards that have quarterly rotating bonus categories into the mix. If you are considering this strategy, make yourself a spreadsheet or get a label maker so that it’s easier to keep track of what card pays for what.

SUB Farming (2-4 per year)

In a nutshell, SUB farming is all about getting those sweet SUBs and then saying “thank u, next.” This can be insanely lucrative for the level of work you’ve got to put in. Those people blogging about how they travel the world in luxury for free all the time? Yeah, this is how they do it. The only difference between this level and that one is the degree to which you’re farming bonuses. At this level, we’re going relatively slow but still looking to cover the expense of flights and/or lodging for a few family vacations a year.

Once you’ve decided that you’d like to farm some SUBs, the first thing you need to do is start a spreadsheet that’s going to detail three things: the card you open, the date you opened it, and the date you received the SUB. This is important because when it comes to SUBs, the different card issuers have different rules surrounding how often they’ll give you one for a given card or family of cards. For example, American Express makes it easy, they’ll give you one SUB per card per lifetime. On the other hand, a bank like Chase might let you get another SUB on a card you’ve previously had after a specified length of time. How will you know when you’re up for round 2 on a card? The spreadsheet!

In addition to telling you when you might be up for another go at a card, having a spreadsheet can also inform you when you might be reaching your limit with certain card issuers. Going back to Chase (just because their rules are better known) you can only open up a certain number of cards in a given time period before they start rejecting your applications. Currently (it can always change) they have a rule that if you’ve opened up 5 personal cards with any bank in the last 24 months, they’ll generally reject any new credit applications you make with them.

And that’s just one of the more famous examples. Each bank or card issuer is going to have its own rules that they generally don’t publish. The only way to navigate the waters here is to keep tabs on what your activity’s been and use forums to keep up to date with what other people have discovered regarding the various limits issuers impose.

Finally, when SUB farming, you need to consider whether the card you’re opening for the SUB is a keeper or one that’ll become dead weight in your wallet. This is all the more important when considering a card with an annual fee. Some cards have cool ongoing benefits that can even make them worth the fee, others not so much. Your job is to separate the wheat from the chaff and come up with an exit strategy for the ones that don’t make the cut.

If you decide the card needs to go, there are a couple of ways to go about it. The first, and obvious one, is to simply close the account, and, believe it or not, there’s a possible downside to this. If the card is an old one, it can negatively impact your credit score by decreasing the average age of your lines of credit. Dumb? Yes, but it’s still a thing. In addition, if you close that card “too soon” (which is not really defined) after you got the SUB, the card issuer might flag the account for misuse and claw back the SUB.

On the upside though, if this is a card you’ve had for a while you might be able to milk another bonus out of it called a “retention bonus.” You will need to actually talk to a human being about this, but it’s possible that in lieu of closing the account, you can get offered the chance for some extra points, a fee waiver, or a statement credit.

What else can you do? Downgrade it! Oftentimes, cards are offered in different tiers, some with an annual fee and perks, others with no fee and fewer perks. Sometimes the better move is to keep the line of credit open with a card that doesn’t have a fee than shutter the account entirely.

2-Player Mode

Do you know what’s better than scoring a nice SUB on a new card? Having your spouse open the same card under their name and scoring yet another SUB. Even better than that? Getting a referral bonus for referring your spouse to the card. That’s 2-player mode.

If you’re married or otherwise financially entwined with another human being, 2-player mode can be a great way to rack up points while keeping either one of you out of trouble from a card opening point of view. Incorporating the rewards game into your financial plan can be great, but only if you steer clear of the dangers listed above and craft a strategy that’s sustainable. 2-player mode helps a lot with the latter.

In addition to helping you keep the party going, 2-player mode also has its own opportunity. Namely, the opportunity to easily take advantage of cardmember referral programs. Most cards offer these. Basically, they give you a link to share with others and if others use that link to open up the card themselves, you get paid. How much you get paid varies, but if the card in question is one of the more premium varieties, the payout is generally larger. For instance, with that SUB I’m finishing out now, my wife referred me to the card and got an extra 15,000 points (which we’ll use for ~$375 in travel expenses) just for emailing me a link. Not bad for a little cut and paste.

You can screw this up though. Ever hear of an “authorized user?” It’s when you add someone to your account, they get their own card to use, and all their purchases go on your bill. Heck, you might even get charged an additional fee every year for having them there.

Don’t do it.

There’s a time and place for making someone an authorized user on your account, but this isn’t it. When you make someone an authorized user on a card, you generally shut them out of getting SUBs on that card. Need to have the card in two places at once? Use a mobile wallet.

Stacking

When you make a purchase, are credit card points the only incentive out there to encourage your spending?

No!

Welcome to the wonderful world of stacking!

Aside from store loyalty programs (which can be part of the stack), there’s a whole cottage industry of commission-sharing companies whose business model is all about getting you to shop places in return for some additional cash or points back on your purchase. Online, these are typically known as shopping portals. Your card issuer might even have its own.

Points or cash back you earn through these sites always earn on top of whatever points your card earns, hence the term stacking. One level of earning through your card might be nice, but add in another (or maybe multiple as we’ll cover later on) and the total rebate you get on your purchases can approach SUB territory.

The way it works is simple. You go to the shopping portal site you have an account with, link to the store you want to shop at through their site, do your shopping, and a few days later some extra cash or points are deposited in your account with the shopping portal. All you have to do is pick the best portal you wish to do business with. And if you think that’s hard, don’t. The interweb has made it easy as a number of sites aggregate the top portals and you can search by store. Personally, I’m a fan of the site Cashback Monitor.

Advanced

Now we get to the more difficult ways to earn points. At this level, your rewards game is more of a side hustle than a hobby. To be successful here, you’ll need to consistently put in the effort to stay on top of new developments in the rewards space and have strong organizational skills.

SUB Farming (5+ Per Year)

While the overall process is pretty much the same as at the intermediate level, SUB farming at the advanced level requires some different considerations and an even greater need to keep tabs on your cards. Personally, I’m not a big fan of SUB farming at this level. But, if you’re wondering how those people with travel-hacking YouTube channels seem to score five-figure plane tickets for free, this is mainly how it’s done.

First off, as you get more aggressive with SUB farming, the closer you get to your business becoming a liability versus an asset for the credit card companies. And, as it turns out, they don’t care to do business with people who want to eat into their bottom line. While there’s no red line where your level of SUB farming activity will get you into trouble, it’s always a concern at this level. Being active in various forums, learning from other people’s experiences, and getting to know intuitively where those lines might have to be central to your strategy here.

Second, this level of SUB farming presents the challenge of picking good cards to target. More than likely, you’ll burn through the most desirable cards early on, leaving you with second and third-tier choices. At that point, you really need to think about what kind of redemption strategy you can use (more on that later) to squeeze value from cards you would’ve passed on otherwise.

Third, many cards (including most of the ones with juicy SUBs) require that you spend a certain amount of money in the first few months in order to qualify for the SUB. This usually isn’t a problem at the intermediate level but can be challenging at the advanced level, especially if you’re making it a point to not inflate your lifestyle. So what do you do once you’ve exhausted the parts of your budget you’d normally put on a card? Look into paying for things like your rent or mortgage with a card. Typically, those types of expenses don’t allow card payments, but there are services that will let you use a card to pay them, usually charging an extra fee to do so. Under normal circumstances, it’s totally not a good idea to pay bills this way. But in this instance, the “return on investment” you get from the SUB might make the juice worth the squeeze.

Finally, just like you need to consider at the intermediate level, determining exit strategies for the various cards you open is super important. If you don’t you’ll soon find yourself buried in annual fees charged by dozens of cards sitting in a drawer. In addition, those retention bonuses I mentioned earlier can play a much bigger role at this level of play as you may find that they’re the only way to squeeze any type of bonus out of a card past a certain point.

Multi-Stacking

How can you earn SUB level rebates on your purchases without having to farm another SUB? Stack a bunch of smaller reward rates and discounts on top of one another! Multi-stacking is kind of like the extreme couponing of the rewards game but you can get similar results without holding up the line at the grocery store.

In addition, multi-stacking doesn’t share many of the same types of risks that SUB farming can have. The primary risk here has to do with your data, as that’s what’s generally paying for all the rewards. Don’t want to share your data with third parties? Don’t play around with stacking.

So how does it work? Generally speaking, there are multiple avenues for stacking discounts outside actual coupons. They are:

- Credit Card Offers

- Shopping Portals

- Active

- Passive

- Gift Card Marketplace

- Brand Loyalty Programs

Each of these things can form part of your stack so let’s talk about each a little more in-depth and then put it together in an example.

When speaking about credit card offers in this context, I’m not talking about the ones that might promise a SUB. Offers in this context refer to various smaller promos you can take advantage of either with specific retailers or spending categories. In general, these offers are found on your credit card account’s online dashboard and you need to opt into them. If used, many of them will give you additional points or a percentage back as a statement credit.

Next, we come back to shopping portals, but this time, I want to break them down into what I call active and passive. Active portals are like the ones described earlier. You have to click a link and shop through that link in order to get the bonus. Passive portals don’t require that. With a passive portal, you supply the portal with read-only access to your card transaction data and when you make a purchase with an affiliate, the bonus gets deposited automatically. Make a purchase through an active portal with a passive affiliate? Yeah, you get both bonuses. And if you use multiple passive portals that don’t share the same network infrastructure, it’s possible to double, triple, or even quadruple dip on the rebates.

Online gift card marketplaces present yet another opportunity to shave some extra percent off your purchases. The premise is simple. People get gift cards that they don’t want all the time and need a place to offload them. However, a gift card is just a form of currency that can only be used in limited settings. Because of that, the market value for gift cards is always lower than that of actual, legal tender currency. So, if someone wants to sell a gift card for, say, dollars, they have to price it at a discount. And depending on the popularity of that gift card’s issuer, that discount might be small, or incredibly steep. In addition, many of these marketplaces often take on the role of new gift card retailers as well, offering cash back on their platforms as an incentive.

Finally, we have the individual retailer’s loyalty program. While many of these might not be worth your time (and data), especially if you don’t shop with them often, it never hurts to consider them. Sometimes, you might even get a welcome bonus just for signing up.

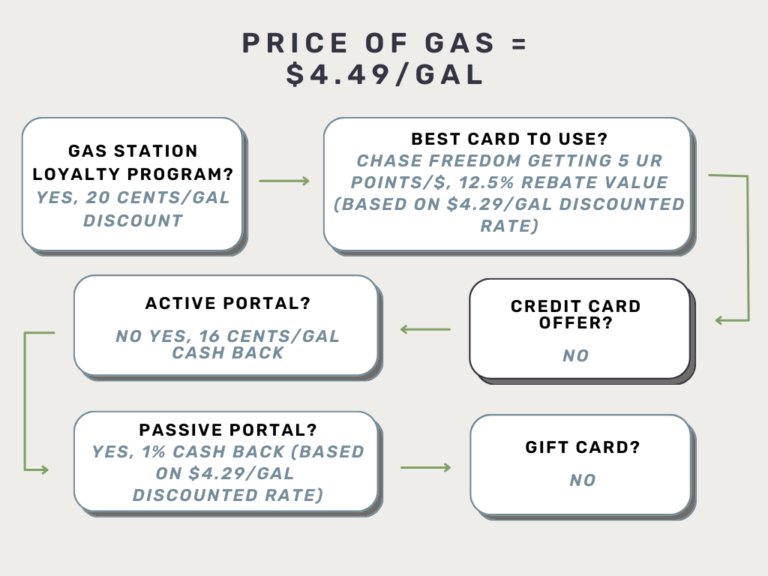

Here’s a personal example of this using a gas station near me, as I write this in July 2022, and how my thought process went.

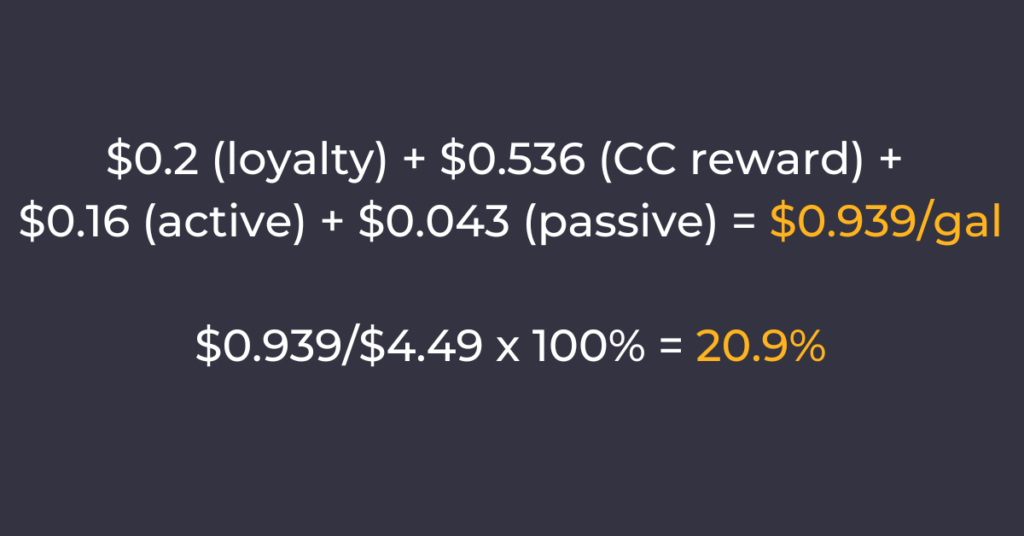

Putting it all together, we get this as a total discount (expressed as a percentage) per gallon:

Not bad, right? That’s the power of multi-stacking.

Redeeming Rewards

Now that we’ve earned a crap ton of points, it’s time to do something with them. Mercifully, redeeming rewards tends to be a lot less complicated than earning them and it’s not difficult to extract a reasonable amount of value from them. Still, there are some things to look out for and some techniques you can use to amp up that value.

Beginner

Cash Back

Redeeming your points for cash back is the absolute easiest way to extract value from them, and depending on your card, it might be the only thing you can do with them. Typically, points redeem at a 1 cent per point value when cashing them out, which isn’t bad; but not great if you can possibly redeem them for travel expenses.

One word of warning here though. Oftentimes, retailers affiliated with card issuers will give you the option to “pay with points” which sounds nice, but it’s usually a trap meant for people who don’t bother to do the math. For example, a very popular online retailer will let me do this with my Chase UR points. But, when you do the math, you find that redeeming them in this way results in a per-point value of $0.008, 20% less than the value I’d get if I just cashed them out!

In addition, that same retailer offers a card giving 5 points back on purchases made with them and the option to pay for future purchases with those points. Sounds reasonable. But, if you pay with the points, you no longer get the 5 points per dollar from the card. Better to redeem those points for actual cash or a statement credit than pay with them once again.

Book Travel With Points

This is typically the only option available to you if you have a card earning airline miles or hotel points and a potential option if you carry one of the bank-issued (Chase, American Express, Citi, etc.) premium cards. For this section, I’m going to focus on the bank cards since there can be more advanced considerations with miles and hotel points.

Nowadays, most of the major card issuers operate their own online travel agencies, and to entice you to use those agencies, they tend to give you a guaranteed bump in the value of your points (typically in the 0.25-0.5 cent per point range) if you use your points to pay for your vacation. Unlike my previous warning about paying with points, in this context, it can be worth it, especially if you’re looking to keep things simple.

Intermediate

Transferring Points

One of the biggest benefits of having a card that earns bank points such as the Chase UR points or American Express Membership Rewards points is the ability to transfer those points to their travel partners. And while each bank has its own list of airlines and hotels that they partner with, the ability to transfer lets you shop around within that list to find the best redemption value when booking a trip.

For example, say you’re looking to book a trip and you don’t really care what airline or hotel you’re going to use. Once you find out how much it’ll cost in points and/or money from each of the options available to you as a transfer partner, you transfer the points to the partner offering the highest value and cost reduction for your trip. Oftentimes, the value you’ll be able to squeeze out of a point will be quite a bit more than the 1 cent per point you’d get from just cashing them out. For my family, we’ve gotten a lot of value from transferring our points out to hotels where we’ve averaged about 2.5 cents per point in value.

One word of warning here. When you transfer points, the process is typically irreversible. Found a better redemption after you transferred a bunch of points to that hotel chain? Guess what? You’re using the points at the hotel. Only transfer points once you are absolutely sure that you’re cool with redeeming them with a given travel partner.

Advanced

Gaming Award Charts

Finally, the last thing we’re going to talk about regarding the rewards game is how some of the pros actually land those ridiculous airline redemptions that seem to pepper social media. While yes, those people accumulate an ungodly amount of points through aggressive SUB farming and the like, they’re also incredibly conscious about squeezing every last cent of value from those points. To do that, they have to think out of the box when it comes to where points get sent.

For example, why might a travel hacker living in New York, with absolutely no interest in traveling to Europe, transfer their hard-earned points to British Airways?

Two reasons: airline alliances and award charts.

Most major airlines today operate in partnerships with other airlines known as alliances. If you’ve done any air travel at all, you’ve probably heard of the big three: Star Alliance, Skyteam, and Oneworld, each founded in part by a major US airline (United, Delta, and American respectively). Within each alliance, partner airlines share resources to help travelers get to their destinations and allow travelers with loyalty benefits on one partner, such as miles and elite status, to enjoy them across the alliance. That last bit is incredibly important to the discussion here.

Within an alliance, it’s possible to book award travel on airlines that you have no award miles with.

But why would you do that? First, maybe the airline you have the miles with just doesn’t go where you’re looking to go. That’s the obvious reason. The less obvious, and more interesting, reason is, maybe the airline you want to use has a crappy award chart.

What’s an award chart? It’s basically the pricing scheme an airline has when you’re looking to book award travel with them. Many of them use a pretty straightforward algorithm where the amount of miles you need to pay is based on the normal cost of the fare. Others are…well, complicated. But that’s where the value tends to be.

For instance, some airlines’ award charts charge a flat rate within a geographic area (like the lower 48 states) while others have a tiered scheme based on distance. Here, an opportunity might exist for the traveler flying from New York to Los Angeles when using the geographic chart. But, if the traveler isn’t going very far, say New York to Baltimore, then using the carrier with the distance-based chart might be the better bet. What’s more, the airline with the better award chart might have nothing to do with the actual flights involved, as long as they’re in an alliance with the carriers that are.

In my experience, gaming the award chart system can be lucrative, but wins weren’t frequent enough for it to be a major part of my rewards game. If you live in/near a major city or airline hub and plan on international or luxury travel, it can produce a lot of return. But, if you live in the country like me, or if your travel is more run-of-the-mill, I wouldn’t expect a ton of value here.

Conclusion

Overall, the rewards game can be well worth playing, as long as you play it responsibly. Play it right, and you can significantly offset parts of your budget. Play it wrong, and there are legit consequences. After all, getting some free flights or vacations means nothing if it means getting yourself in credit card debt or derailing your financial plan with excessive spending.

But if you do think the rewards game can benefit you, I encourage you to try it out. Even at the beginner levels of play, it can help make a dent in your expenses. And, sure, as Dave Ramsey likes to point out “no one ever says they got rich off credit card points” (and he’s 100% correct on that), that’s not really what we’re getting at here either. The rewards game isn’t something that’s ever going to play the lead in your financial plan. But it can play a fun supporting role.

Interested in checking out some credit cards that offer rewards? Click on the links below!

Featured 2023 Credit Card Offers